Can artificial intelligence creation be regarded as art?

From painting to AI-generated podcast conversations to screenwriting, there is a concerted effort to replace human creativity with computer automation while discarding the concept of art as we know it. "Jacobin" author Luke Savage used the 2013 movie "Tim's Vermeer" as an example to discuss a series of issues behind artificial intelligence-generated art and the ideas conveyed behind it.

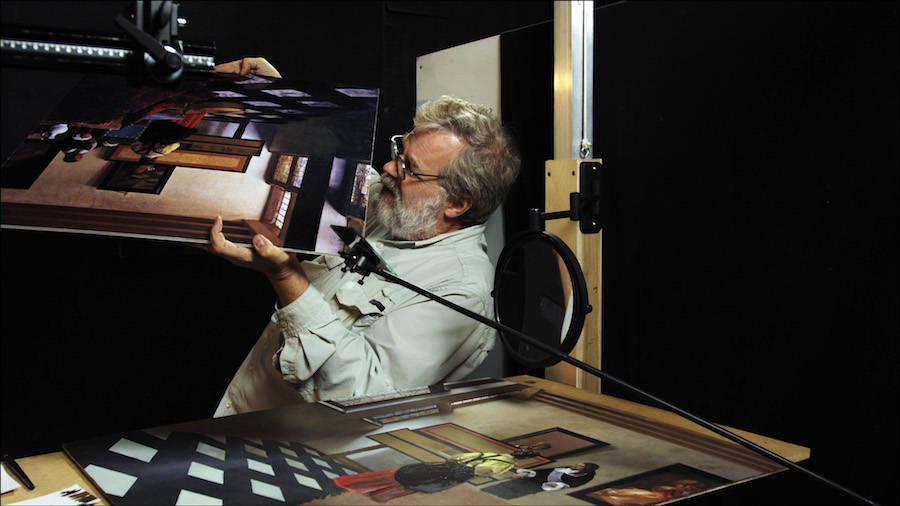

In the film Tim of Vermeer, actor Penn Gillette documents how his friend Tim Jenison recreates the 17th-century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. Techniques of Johannes Vermeer. To do this, Jenison, a software executive and visual engineer, developed a series of sophisticated methods that used mirrors and light to replicate Vermeer's technique and recreate his signature depth of field and chromatic aberration.

Stills from "Tim's Vermeer"

Jennison made an impressive effort to replicate Vermeer’s 1660s work The Music Lesson. However, Jennison and Gillette appear to have misunderstood what they were doing. Gillette gushed about the "photographic" and "cinematic" qualities of Vermeer's work, but failed to capture its playful and abstract dimension, as he enthused: "My friend Tim painted a A painting by Vermeer! He painted a painting by Vermeer!” But this reproduction is nothing more than an extremely sophisticated experiment in digital painting, a derivative simulacra of beauty.

This sentence can be rewritten as: The two actors regarded Vermeer's work as a craft and technique, and they strived to present a true sense of reality in their performances. In this understanding, Vermeer's works do not involve social or cultural processes, have no inspiration other than the act of mechanical production, and have no other purpose at all except the characteristics of photographic realism. This approach seems to be similar to the artistic creation of artificial intelligence.

Luke Savage pointed out: Like any technology-driven industrial process, artificial intelligence may ultimately have profound social and material impacts. But in the final analysis, artificial intelligence has the necessary conditions to drive capitalism since the 19th century, which is the continuous pursuit of more efficient production at lower costs. This development is a threat to artists and cultural workers. As artist Molly Crabapple observes, existing apps like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney can already generate detailed images based on text prompts for next to no money. "While these images are still problematic and somewhat soulless, they are faster and cheaper," she writes. While the AI sometimes drew extra fingers or the wrong bump in the ear, overall it has achieved great results. Many illustrators earn money by creating images for book covers and editorial illustrations. ”

In the cultural field, cultural products will become extremely crude: fake paintings produced by computers may be sold in artificially created scarcity markets such as cryptocurrency or non-fungible tokens (NFT), and virtualization may be made virtual through algorithms. Pop stars record formulaic music. Eventually, authors will be replaced by generative algorithms. These algorithms reduce differences in dialogue and plot structure while reducing author involvement. According to Luke Savage, the promoters of artificial intelligence culture mistakenly regard copying as creation, and equate realism with artistic expression. In this conception, creativity is ultimately a mechanical endeavor, and every art: painting, film, music, poetry, is nothing more than a collection of granular data points; "art" is, quite literally, the individual components The sum of its parts.

Accelerated by the monopoly of technology companies, mass entertainment has increasingly become a wasteland of derivatives and algorithm-generated "content" - with almost no meaningful new content. With the help of technology, corporations have honed a zombified model of cultural production in which existing intellectual property (IP) is endlessly recycled and regenerated into sequels, prequels, remakes, and Poor imitations and other forms were mass-produced. To the extent that AI represents a revolution, it will perfect this process, which is not really a revolution at all.

Determining whether a certain work of art is good or bad is tortuous and complicated. While the creative process becomes more efficient, that doesn't guarantee it gets better.

Art, music, almost all of human life and thought transcend basic matters like sleeping and eating, emanating an essence or spirit that cannot be reduced to a mechanical process, no matter what we decide to call it ( Wisdom, humanism, creativity, soul). By definition, it produces something that cannot be quantified or categorized. Once a painting or piece of music has been created, it can be broken down into its component elements, which in turn can be rearranged or reconfigured to produce something else. However, unless some new creative element is introduced, the result of "innovation" will always be a fake copy.

Quoted article:

https://jacobin.com/2023/05/ai-artificial-intelligence-art-creativity-reproduction-capitalism

Surveillance Controversy in Western Workplaces

In September 2020, a reporter from Vice magazine discovered that Amazon was hiring two "intelligence analysts" for its Global Security Operations (GSO). Analysts will employ data analysis and other tools to detect and resist "labor organization threats" and other political opposition actions against Amazon. This ubiquitous employee surveillance has sparked employee outcry and backlash. In 2022, Amazon warehouse workers in Staten Island formed a union and publicly expressed their dissatisfaction with continuous work monitoring.

Over the past decade or so, scholars, journalists, and technology leaders have continued to focus on how digital technologies will transform work. In an article in the Boston Review of Books, Brishen Rogers, an associate professor at Temple University's Beasley School of Law, reports on this phenomenon. Researchers believe that digital technology has two different applications. Automating tasks is one way to replace specific workers, while another is discriminating against workers based on factors such as race, gender, national origin or disability. But in today’s vast service economy, some companies are harnessing digital technologies as tools of domination, using them to limit employee wage increases, prevent workers from forming unions, and increase labor exploitation. Workers’ resistance to digital surveillance represents their call for transparency and democratization of digital technologies in the workplace.

On May 31, 2023 local time, in the United States, Amazon and its subsidiaries will pay more than US$30 million for accusations of violating user privacy.

The conflict between corporate surveillance and workers is not new. For more than a century, companies have tried to generate, capture, and quantify information about workers and work processes to drive down wages. After a long struggle, employers took away production control from workers, streamlined and informatized production skills, and formulated so-called "laws" that bound output rates and wages.

With the advent of telegraphs, telephones, fax machines and modern information technology, companies have realized remote supervision of their workforce. Corporate surveillance capabilities have expanded dramatically in recent decades as corporate intranets, mobile computing, location tracking, image and natural language recognition, and other forms of advanced data analytics have matured. Today's companies crave constant monitoring of all aspects of work and production, and such monitoring is also asymmetric: Companies can monitor employees without their knowledge, while preventing employees from monitoring management.

Currently, the retail, food service, logistics, hospitality and healthcare industries are among the largest employers in many countries. These companies employ large numbers of workers, but productivity growth is slow because producing their products requires labor or attention that is difficult to increase through technology. So these companies are very concerned about containing wage growth. Many companies adopt business models with high employment, low skills and high turnover, and use new technologies to prevent workers from forming collective power.

According to Brishen Rogers, companies use data to constrain employees in three different ways; he calls the first one "digital Taylorism", which uses a scientific management system to establish management control of the labor process. Digital Taylorism includes various forms of automation and heightened surveillance. In the case of Amazon warehouses, algorithmic monitoring systems report employees who don't perform quickly enough or who use the bathroom without a manager's permission, sometimes even recommending they be fired.

Companies go beyond digital Taylorism to use surveillance and data aggregation technologies to guard against unionization and other collective action. For example, companies could use new hiring algorithms that aggregate candidates’ work histories with data on social media posts or political behavior to screen out employees who might challenge management’s authority. Building trust and solidarity is a vital part of the worker organizing process, with workers engaging in collective action to protect each other and share responsibility. But modern surveillance can prevent this mobilization. First, workers who are constantly supervised and separated from each other have little opportunity to achieve common goals. Additionally, developments in speech processing and natural language processing software allow companies to "hear" almost everything said in the workplace and see when workers are talking to each other.

Finally, many companies are using new technologies to change the scope of their business. They hire workers by purchasing labor, treating workers as independent contractors rather than legal employees. Amazon, for example, outsources its delivery operations to various outside companies, but as one reporter discovered, Amazon's contract requires service providers to "provide Amazon with physical access to its premises, as well as various Data, such as geographical location, the speed of movement of the driver's vehicle, etc. Amazon said it has the right to use this information as it wishes. Without liability and cost, Amazon can still exercise traditional employment rights and take supervisory measures.

Given the vast technological capabilities of today’s employers, policymakers may want to consider banning long-standing and seemingly uncontroversial forms of workplace surveillance, such as monitoring workers on the shop floor while they work. Advocates have begun exploring ways to partially or completely eliminate workplace data. For example, researchers at the University of California Berkeley Labor Center, after extensive consultations with academics, unions and others, recommend banning the use of facial recognition and algorithms to identify workers’ emotions in the workplace and limiting employers’ Collect worker data that is “necessary and essential to the worker’s work.” The researchers also recommended that employers should only use electronic monitoring "if necessary to accomplish core business tasks, protect worker safety, or comply with legal obligations."

Brishen Rogers said such reform would require a more fundamental change in labor law: reducing the power of employers to choose and implement workplace surveillance technologies and giving workers a real say in production planning and execution. Three categories of reforms to data practices could advance these goals: banning data collection and use in various contexts, deliberation of data practices in other contexts, and placing data sources or technologies under public or social control.

In addition to the ban on data collection mentioned above, Brishen Rogers proposed that Congress could consider giving workers some collective rights, regardless of whether they belong to a union, to consult on technological changes. Workers and the public deserve greater control over data and related technologies, so Congress should pass reforms to socialize data as a public resource. For example, Congress could require companies to share the data they collect about workers and work processes. Regulators or workers' rights groups can then analyze this data to detect violations of basic labor laws, such as noncompliance with wages and hours. Under such reforms, workers will have more bargaining leverage. However, given employers' wariness of workers taking power, such reforms will be no easy task. Many tech companies and service industry giants will find ways to circumvent restrictions and continue to closely monitor their employees in their own ways.

Quoted article:

https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/workplace-data-is-a-tool-of-class-warfare/

The above is the detailed content of The Paper Weekly丨Can artificial intelligence create art? Controversy over surveillance in Western workplaces. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!

The advantages of OTC trading

The advantages of OTC trading

attributeusage

attributeusage

What is the difference between pass by value and pass by reference in java

What is the difference between pass by value and pass by reference in java

How to operate json with jquery

How to operate json with jquery

How to eliminate html code

How to eliminate html code

Win7 prompts that application data cannot be accessed. Solution

Win7 prompts that application data cannot be accessed. Solution

Commonly used mysql management tools

Commonly used mysql management tools

how to build a website

how to build a website