After five years of "confrontational cooperation", consciousness theorists successfully presented a stage showdown in front of the audience. Although this duel did not determine the final outcome, it is still regarded as a progress in the history of science

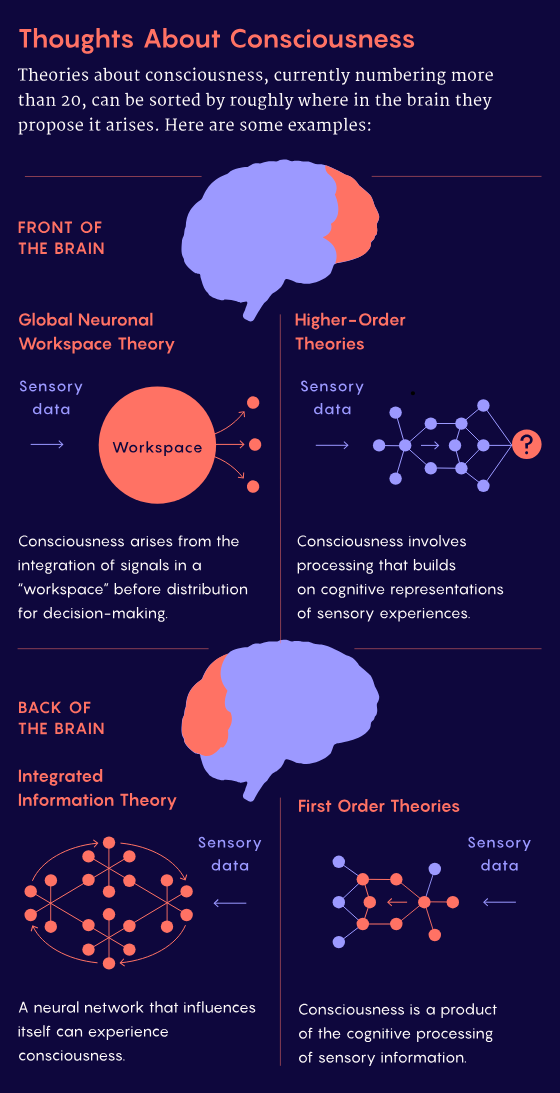

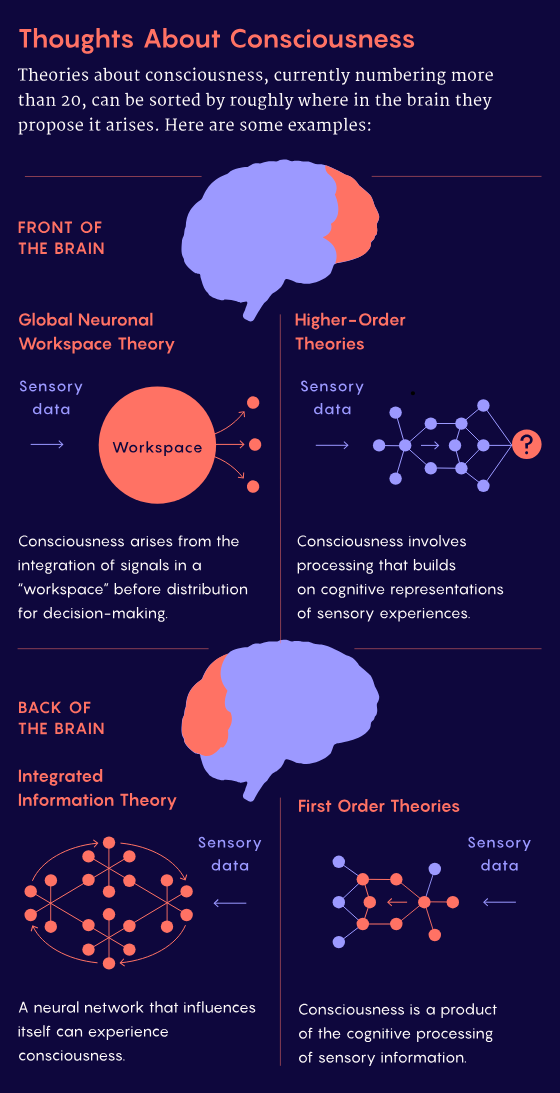

In the scientific world, theories are often There are endless ones, but after the torture of data, only a few remain. In the fledgling science of consciousness, a dominant theory has yet to emerge. More than 20 theories still battle it out in this arena.

This current situation is not due to lack of data. Ever since Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the DNA double helix, took up consciousness as a subject of research more than three decades ago, researchers have used a variety of advanced techniques to probe the brains of subjects, tracking what could reveal consciousness characteristics of neural activity. The wealth of data produced so far should at least disprove those theories.

Five years ago, the Templeton World Charity Foundation launched a series of adversarial collaborations to advance theory screening efforts. In June this year, the first results from this collaboration pitted two high-profile theories against each other: Global Neuronal Workspace Theory (GNWT) and Integrated Information Theory (IIT). Neither theory emerged as the winner.

This result, like the results announced at the 26th meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (ASSC) in New York, was also used to settle Crick A 25-year bet between longtime collaborators, neuroscientist Christof Koch of the Allen Institute for Brain Science, and New York University philosopher David Chalmers, who coined the term “the hard problem” to describe people The hypothesis that the subjective sense of consciousness can be explained by analyzing brain circuits.

##

##

Since the first fusion of consciousness versus cooperation is a victory for science, neuroscientist Christof Koch of the Allen Institute for Brain Science believes.

On the stage at NYU’s Skirball Center, following rock music, a rap performance about consciousness and a presentation of a series of research findings, Koch, The neuroscientist bets philosophers that the neural correlates of consciousness are not yet certain.

Still, Koch declared: This is a victory for science.

But is it really so? The project received mixed reviews. Some researchers note that meaningful testing of the differences between the two theories has not yet been possible. But others highlighted the project's contribution in moving the science of consciousness forward: providing large, novel, normative data sets, and inspiring other entrants to engage in their own adversarial collaborations.

The relevance of consciousness

When Crick and Koch published in 1990 With their landmark paper, "Toward a Neurobiological Theory of Consciousness," their goal was to put consciousness—which had been dominated by philosophers for 2,000 years—on a scientific basis. They argue that consciousness as a whole is too broad and controversial a concept to serve as a fundamental starting point.

Instead, they focus on a scientifically tractable aspect of consciousness: visual perception, that is, the conscious acquisition of visual information about the color red, for example. Their goal is to find neural correlates of this phenomenon, or as they call it, neural correlates of consciousness.

#The first stages of decoding visual perception are already fertile ground for scientific research. Light falling on the retina sends a signal to the visual cortex of the brain. There, more than 12 different neural modules process signals that correspond to edges, color, and motion in the image. Their outputs combine to build the final dynamic picture of what we see.

The value of visual perception to Crick and Koch was that the final link in the chain—consciousness—could be separated from the other links. Since the 1970s, neuroscientists have known about people with blindsight, who have no vision because of brain damage but who can navigate a room without encountering obstacles. While they retain the ability to process the image, they lose the ability to be aware of it.

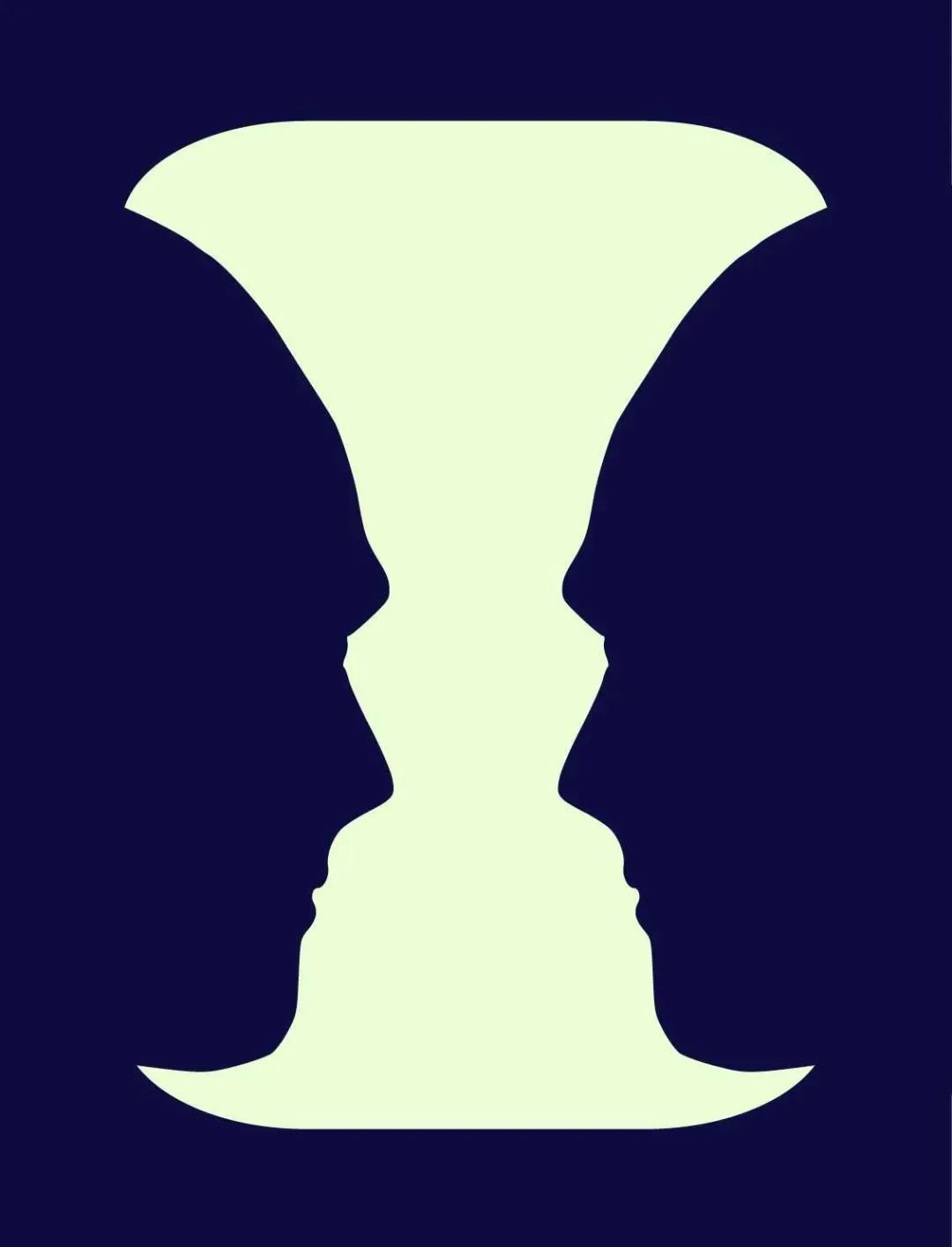

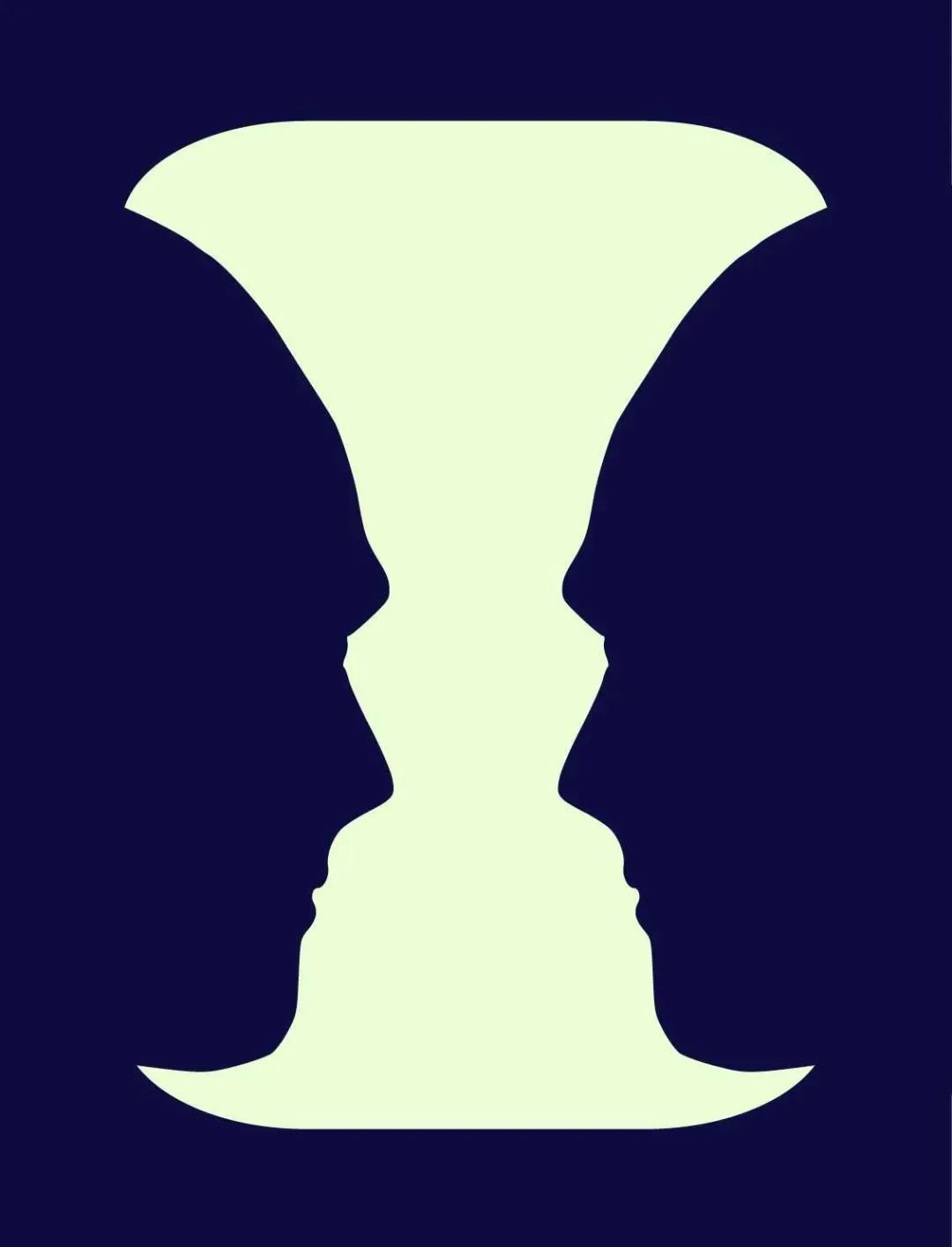

In this famous hallucination picture, the brain's consciousness-generating mechanism allows us to experience the image as a vase or as two faces—but not both at the same time.--Nevit Dilmen

In this famous hallucination picture, the brain's consciousness-generating mechanism allows us to experience the image as a vase or as two faces—but not both at the same time.--Nevit Dilmen

We can all experience this form of disconnection. To take a well-known optical illusion, the image above could be seen as a vase or two faces. At any time, we can only see it as one or the other. The way our brains process perception prevents us from being aware of both at the same time.

Experimental psychologists can exploit this disconnect through the phenomenon of binocular rivalry. Our brain can usually effortlessly combine the slightly different overlapping images it receives from the left and right eyes. But if the images are very different, rather than merged, they become competitors: first one dominates our perception, and only then does the other take its turn. When neuroscientist Nikos Logothetis of the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics described the phenomenon of binocular rivalry in 1996, Crick was so excited that neural correlates of consciousness would be found by the end of the 20th century. (This enthusiasm led to Koch's bet with Chalmers.)

Over the past two decades, brain scanners have become increasingly sophisticated, and subjects' Perception can already be manipulated during consciousness research. The trickle of data has grown exponentially, but instead of being washed away, the theory of consciousness in the river has multiplied.

One way to divide these theories is that some of them, such as GNWT, believe that consciousness requires the participation of the cognitive part of the brain, that is, we "think" places, while IIT theorists and others claim that neural correlations depend on the areas of the brain involved in perception, that is, where we "feel". These ideas are often intuitively described as "front-of-brain" versus "back-of-brain" theories (although the actual anatomical distinction is more imprecise and boring than that). This intriguing distinction echoes the ancient philosophical analysis, that is, whether consciousness is related to thinking, as Descartes said, "I think, therefore I am," or whether it is "irrelevant to thinking," such as meditation and yoga. Thought.

## According to advocate Stanislas Dehaene, a neuroscientist at the Collège de France, thinking is a core part of the conscious state. Referring to IIT, he said: This is a huge difference between the two theories. I don't believe there is pure consciousness.

GNWT insists that when we process information unconsciously, a small part of the information can enter the conscious workspace through a channel. Within this space, information is integrated and passed to other brain areas, making it available globally for decision-making and learning. Stanislas Dehaene said: This workspace takes on the mission of performing functions. Since decision-making and learning are the responsibility of the prefrontal cortex, the front part of the brain is considered critical to consciousness.

This idea germinated as early as 1988 in the mind of psychologist Bernard Baars, who currently works at the Society for the Science of Mind. He saw similarities with the blackboard, an early artificial intelligence system architecture, in which independent programs could share information. Dehaene then connected this conceptual template to findings from cutting-edge neuroscience and used computational modeling to develop GNWT.

#IIT does not draw analogy with artificial intelligence architecture. Giulio Tononi, a neuroscientist and psychiatrist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed the theory of IIT starting from five axioms about consciousness: consciousness is inherent to the entity that possesses it; the composition of consciousness is structured; Information is rich; consciousness is integrated and irreducible to components; consciousness is independent of other experiences. He then developed mathematical descriptions to fit these axioms. For Tononi and other IIT theorists, the neural structures most consistent with these mathematical descriptions are grid-like architectures associated with sensory areas, which they call hot zones.

Giulio Tononi, a neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed a comprehensive information theory by mathematically formulating five axioms about consciousness. — John Maniaci / University of Washington Health , there are currently other forebrain concepts of cognitive styles, including several higher-order theories (HOT) and active reasoning theories, as well as various hindbrain concepts, such as first-order theories and local representation theories.

Although it is said that some of these theories can be falsified by comparing the data of living brains with the theoretical predictions to see if they are consistent. But unfortunately, that's not the case.

Looking across the horizon becomes a ridge and the side becomes a peak

Over the years, researchers have designed A series of clever experiments in which subjects report when they are aware of an object while using some psychological trick or illusion to distract them. These results suggest that conscious perception is associated with activity in the prefrontal cortex, which favors GNWT or other frontal brain theories. But philosophers and experimenters have also raised concerns that the studies may be measuring neural activity associated with reporting tasks, rather than consciousness itself.

Therefore, the scientific research community developed the non-reporting paradigm as a solution, which is binocular rivalry. If a test subject's left eye sees a face moving to the left and their right eye sees a house moving to the right, their conscious perception flips between the two images. Researchers can identify perceived images without reporting them by tracking the way their eyes move. Data from that time suggested that in these reporting-free paradigms, the signals for conscious perception were located in the back of the brain.

#However, theorists are rarely easily convinced by experiments and data. In a 2016 review, the IIT camp dismissed the report-based experiments as methodologically flawed. But in 2017, the debate continued, with several competing articles published in the Journal of Neuroscience. In one of the articles, Hakwan Lau, now at the Riken Brain Science Research Center in Japan, and colleagues countered that the no-reporting paradigm is inherently fraught with confusing variables.

#To further complicate matters, experimental results depend on the type of brain recording technology used. This is not surprising, as each technology provides a different perspective on the brain. For example, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can track blood flow and provide good spatial resolution, but is too slow to keep up with the speed of communication between neurons. Magnetoencephalography (MEG), on the other hand, can track the brain's tremors but has poor spatial resolution. Whether researchers measure signal strength at specific locations in the brain or analyze patterns in broader areas also makes a difference.

The result is that, despite the vast amounts of experimental data collected to study the correlates of consciousness, uncertainty gives theorists the opportunity to claim that the data supports their endorsed theories. space.

Tel Aviv University neuroscientist Liad Mudrik believes part of the problem lies in the way the studies were designed. A recent survey by her doctoral student Itay Yaron looked at more than 400 published experiments on consciousness and found that it was largely possible to predict which theory would be supported based solely on the experimental design, without knowing any of the results.

Tel Aviv University neuroscientist Liad Mudrik (left) and her doctoral student Itay Yaron (right) have gathered evidence that using experimental studies The goal of testing theories of consciousness is often thwarted by biases latent in experimental designs. ——Sophie Kelly

Confrontational cooperation

five A few years ago, Dawid Potgieter, head of special projects at Templeton World Philanthropy, was surprised to find that there were still so many viable theories about consciousness. He believed the time had come to do something about it.

#Koch suggested a head-to-head confrontation, a method sometimes used to resolve disputes in physics and with precedent in psychology. In the 1980s, Dan Kahneman, a psychology researcher at Princeton University, coined the term adversarial collaboration to describe the practice of scientists with opposing views working together to develop experiments. By working together, they can eliminate differences in goals and methods that could undermine the conclusion of the work.

Five years ago, Dawid Potgieter convened a symposium on behalf of Templeton World Philanthropy to develop adversarial collaborations to test theories of consciousness. ——Templeton World Charitable Foundation

Potgieter would love to try this. In March 2018, he and Koch held a weekend workshop for 14 participants at the Allen Institute in Seattle. These include three theorists—Dehaene, Tononi, and Lau, who are advocates of HOT—as well as Chalmers and two other philosophers, four psychologists, two neuroscientists, a neuroscientist, and a Potgieter on behalf of the Purton Foundation. Their job is to collaborate on designing new experiments that eliminate all problems of the past and clearly distinguish between different theories.

Three of the psychologists—Mudrik and Lucia Melloni of the Max Planck Institute and Michael Pitts of Portland Community College—have already conducted research in the past challenges to the theory of consciousness. Pitts recalled: One day, I remembered that Giulio had suggested, why don't the three of you lead this project? We had no idea what we were doing. It eats away at our lives.

Over the next nine months, discussions continued. The theorists dug into their theories and came up with new predictions -- one of the collaboration's novel contributions. Mudrik was impressed by his opponents' willingness to negotiate. She said: It takes a lot of courage; it's an adventure.

The research team came up with two experimental designs to differentiate the predictions of IIT and GNWT. They never arrived at predictions different enough to distinguish GNWTs from HOTs, so HOTs were left to another adversarial collaboration between Lau and New York University philosopher Ned Block, a champion of first-order theory.

Tononi paid special attention to the design of the first experiment between GNWT and IIT. Because the given task has caused problems in past experiments, it will be possible to address these problems by changing the task to see how this affects conscious perception.

#Experimental subjects will see a series of different images, such as faces, clocks, and letters in different fonts. They saw each image for 0.5 to 1.5 seconds. At the beginning of each series of images, two specific images were defined as targets (e.g., a woman's face and a retro clock), and subjects were asked to press the Next button. Therefore, other faces and objects in the image will be relevant to the task (because they belong to the same category as the target), but need not be reported. Other types of images in the series, such as letters and nonsense symbols, were not relevant to the task. The test was performed iteratively using different targets in the series so that each set of stimuli could be tested simultaneously as task-relevant and task-irrelevant. State-of-the-art brain signal decoders will link neural firing patterns to what subjects see.

#GNWT’s prediction is that the brain patterns corresponding to consciously perceiving an object will be similar regardless of whether the task is involved. The brain decoder should be able to identify unique signals related to the target image, independent of the task. In addition, it should be possible to detect the "ignition signal" of a new conscious perception entering the brain's workspace and the "off signal" to clear it.

On the other hand, IIT predicts that the brain's mode of awareness will change depending on the task, since performing the task requires the involvement of the prefrontal cortex, while the perception of the peeled-off task requires unnecessary. This pure awareness requires only the sensory hot spots in the back of the brain. The connectivity and duration of the image awareness signal will match the duration of the visual stimulus.

Daniel Kahneman, a psychology researcher at Princeton University, is a firm believer in the value of adversarial collaboration in advancing science, even though he has found that the results of collaboration rarely change an opponent's mind. —Roger Parkes

Dehaene preferred the second experiment, which involved comprehensive decoding of brain patterns. While the subjects played a Tetris-like video game, they randomly saw faces and objects flash across the screen. Shortly after an image appeared, the game stopped and subjects were asked whether they had seen the image. Dehaene prefers this design because it provides a clearer contrast between conscious and unconscious mental states, which he believes is crucial for obtaining clear data on factors related to consciousness.

Because Kahneman was familiar with adversarial collaboration, he mentored the leaders of the three projects. But he also warned them that based on his experience, opponents will not change their minds after seeing the results of cooperation. Instead, he said, when faced with an inconvenient outcome, their IQs jumped 15 points as they invented ways to fit the new, conflicting data.

The researchers began following the workshop team’s recommendations conduct experiment. Tononi’s favorite experiment with GNWT and IIT (testing with different levels of tasks) was completed first. The experiment was performed in two different laboratories using functional magnetic resonance imaging, magnetoencephalography, and intracranial electroencephalography. A total of 6 theory-neutral laboratories and 250 test subjects participated.

On the evening of June 23, a group of excited spectators gathered at New York University to observe the results of the experiment. The results were displayed on a giant screen as a chart highlighted in red and green, as if the researchers were reporting on an obstacle course with three obstacles.

#The first hurdle is to examine how well each theory decodes the categories of objects that subjects see in the images they are presented with. Both theories perform well here, but IIT is better at identifying the orientation of objects.

The second obstacle is the test of signal timing. IIT predicts continued synchronized firing of hot zones during states of consciousness. While the signal persists, it doesn't stay in sync. GNWT predicts that the workspace will "ignite", followed by a second peak when the stimulus disappears. Only the initial spike is detected. In the screen ratings of NYU viewers, IIT was far ahead.

The third barrier involves the brain’s overall connectivity. GNWT scores higher than IIT here, mainly because some analyzes of the results support GNWT predictions, while the signal is not synchronized across the hot zone.

Apparently both theories are challenged by the results. But in the final tally on the event screen, IIT received more green highlights than GNWT and the crowd reacted as if a winner had been crowned. Melanie Boly of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a supporter of IIT, was quite pleased with the results, announcing on stage that the results confirmed IIT's overall claim that posterior cortical areas are sufficient to produce consciousness, and that "the prefrontal cortex's Participate" also does not require global broadcast.

## Stanislas Dehane, a neuroscience at the French College, proposed the theory of the global neuron work space. He believes that thinking is the core part of consciousness.

When Dehaene took the stage, he didn’t admit defeat either. "I decided to follow Dan Kahneman's advice," he quipped. At the same time, he seemed very happy because the most interesting part of this experiment was the task-irrelevant stimulation of consciousness. The question now is whether experiments can show that consciousness can be ignited in the frontal lobes of the brain. "The answer is yes!" he said.

Later, Dehaene suggested that the bar for IITs would be lower than that set by his theory. The complex mathematical core of [IITs] is not really tested, he said. As Block pointed out in his talk that night, the findings supporting the back-of-the-brain theory don't exactly support IIT.

Although IITs received a slightly higher green score, the project leader himself insisted there was no winner. "These results confirm some of the predictions of IIT and GNWT, while significantly challenging both theories," they wrote in a description.

#So has science progressed? Not everyone thinks so.

Some researchers, such as Olivia Carter, a psychologist at the University of Melbourne and former ASSC president, believe the two theories are too different to meaningfully compare their predictions . "My personal feeling is that they are testing something completely different," she said. "IIT focuses on phenomenal content, while GNWT is more interested in memory and attention."

This evaluation seems appropriate. However, it is also somewhat frustrating given that the original stated purpose of adversarial cooperation was to make decisive comparisons. If you want to say that this result is a victory for science, then it seems that it can only be said to have reached the passing line.

Monash University philosopher Jakob Hohwy, a member of another Templeton-funded adversarial collaboration, sees it differently. "This involves the philosophy of science," he said. He notes that the field remains divided over fundamental questions such as whether consciousness is defined closer to thinking or feeling, and even whether subjects' self-reported results actually confound the data. For Hohwy, this collaborative effort is the way forward. "We will find out when we engage in this type of adversarial cooperation," he said.

Others, like Megan Peters, a computational neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, were outraged by media coverage that framed the results as a tie between GNWT and IIT. A horse race, rather than a field with multiple competitors. Peters said it's important to see that science progresses by learning from every experimental hurdle, rather than just focusing on who is the winner and who is the loser.

Nonetheless, Peters remains keen on adversarial collaboration.

The first adversarial collaboration on consciousness may not have succeeded in sifting out any theories in the field. But it does force theorists to make more specific predictions and experimentalists to develop new technologies. "The results of the collaboration remain extremely valuable," University of Sussex neuroscientist Anil Seth wrote in comments after the event in June. "They will advance IIT and GNWT and other theories of consciousness by providing new constraints and new explanatory goals."

For Melloni, opponents have not changed their minds. This fact does not detract from the value of the process. As Kahneman puts it, people don't change their minds, but the way they respond to challenges can cause their theories to advance or deteriorate, she said. "If it's the latter, over time, the theory will die out and scientists will give up on it."

https://www.quantamagazine.org/what-a-contest-of-consciousness-theories-really-proved-20230824/

The above is the detailed content of The debate over 20-plus theories of consciousness remains inconclusive: Five years on, no one theory has dominated. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!

##

## In this famous hallucination picture, the brain's consciousness-generating mechanism allows us to experience the image as a vase or as two faces—but not both at the same time.--Nevit Dilmen

In this famous hallucination picture, the brain's consciousness-generating mechanism allows us to experience the image as a vase or as two faces—but not both at the same time.--Nevit Dilmen