우리는 현재 dev.to 프런트엔드 챌린지를 3D 시각화를 위한 기본 정적 파일 웹 앱을 신속하게 구성하는 방법을 탐색하는 수단으로 사용할 것입니다. 우리는 THREE.js(내가 가장 좋아하는 라이브러리 중 하나)를 사용하여 챌린지의 마크업 입력을 표시하는 데 사용할 수 있는 기본 태양계 도구를 구성할 것입니다.

이 프로젝트에 영감을 준 현재 dev.to 챌린지는 다음과 같습니다.

https://dev.to/challenges/frontend-2024-09-04

이러한 라인에 따라 얼마나 빨리 조합할 수 있는지 봅시다!

새로운 Github 프로젝트에서 Vite를 사용하여 매우 빠른 반복을 위해 즉시 사용 가능한 핫 모듈 교체(또는 HMR)를 통해 프로젝트를 시작하고 실행할 것입니다.

git clone [url] cd [folder] yarn create vite --template vanilla .

이렇게 하면 즉시 작동하는 프레임워크 없는 Vite 프로젝트가 생성됩니다. 종속성을 설치하고 3개를 추가한 후 "라이브" 개발 프로젝트를 실행하기만 하면 됩니다.

yarn install yarn add three yarn run dev

이를 통해 거의 실시간으로 개발하고 디버깅할 수 있는 "라이브" 버전이 제공됩니다. 이제 들어가서 물건을 뜯어낼 준비가 되었습니다!

THREE를 한번도 사용해본 적이 없다면 알아둘 만한 몇 가지 사항이 있습니다.

엔진 설계에는 일반적으로 특정 시간에 세 가지 활동 또는 루프가 진행됩니다. 세 가지가 모두 순차적으로 수행된다면 이는 핵심 "게임 루프"에 세 가지 활동의 순서가 있음을 의미합니다.

일종의 사용자 입력 폴링이나 처리해야 하는 이벤트가 있습니다

렌더링 호출 자체가 있습니다

일종의 내부 논리/업데이트 동작이 있습니다

네트워킹과 같은 것(예: 업데이트 패킷 수신)은 (사용자 작업과 같이) 애플리케이션 상태의 일부 업데이트로 전파되어야 하는 이벤트를 트리거하므로 여기서 입력으로 처리될 수 있습니다.

물론 그 밑에는 상태 자체에 대한 표현이 있습니다. ECS를 사용하는 경우 이는 구성요소 테이블 세트일 수 있습니다. 우리의 경우 이는 주로 3개 객체(예: Scene 인스턴스)의 인스턴스화로 시작됩니다.

이를 염두에 두고 앱의 기본 자리 표시자를 작성해 보겠습니다.

최상위 index.html을 리팩토링하는 것부터 시작하겠습니다.

정적 파일 참조는 필요하지 않습니다

자바스크립트 후크는 필요하지 않습니다

우리는 전역 범위의 스타일시트를 원합니다

ES6 모듈을 HTML의 최상위 진입점으로 연결하려고 합니다

최상위 index.html 파일은 다음과 같습니다.

<!doctype html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8" /> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" /> <title>Vite App</title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="index.css" type="text/css" /> <script type="module" src="index.mjs"></script> </head> <body> </body> </html>

전역 범위 스타일시트에서는 본문이 패딩, 여백 또는 오버플로 없이 전체 화면을 차지하도록 지정합니다.

body {

width: 100vw;

height: 100vh;

overflow: hidden;

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

}

이제 나머지를 정리하는 동안 앱이 작동하는지 확인하기 위한 기본 자리 표시자 콘텐츠와 함께 ES6 모듈을 추가할 준비가 되었습니다.

/**

* index.mjs

*/

function onWindowLoad(event) {

console.log("Window loaded", event);

}

window.addEventListener("load", onWindowLoad);

이제 꺼내기 시작할 수 있습니다! 다음 항목을 삭제합니다:

main.js

javascript.svg

counter.js

공개/

style.css

물론, 브라우저에서 '라이브' 보기를 보면 비어 있을 것입니다. 하지만 괜찮아요! 이제 3D로 전환할 준비가 되었습니다.

3개의 고전적인 "hello world" 회전 큐브를 설명하는 것부터 시작하겠습니다. 나머지 로직은 이전 단계에서 생성한 ES6 모듈 내에 있습니다. 먼저 다음 3개를 가져와야 합니다.

import * as THREE from "three";

그런데 이제 어쩌지?

THREE에는 간단하면서도 강력한 특정 그래픽 파이프라인이 있습니다. 고려해야 할 몇 가지 요소가 있습니다:

한 장면

카메라

자체 렌더링 대상(제공되지 않은 경우)과 장면과 카메라를 매개변수로 사용하는 render() 메서드가 있는 렌더러

장면은 단지 최상위 장면 그래프 노드입니다. 해당 노드는 세 가지 흥미로운 속성의 조합입니다.

변환(상위 노드에서) 및 하위 배열

정점 버퍼 내용과 구조(그리고 인덱스 버퍼, 기본적으로 메시를 정의하는 수치 데이터)를 정의하는 지오메트리

GPU가 기하학 데이터를 처리하고 렌더링하는 방법을 정의하는 자료

따라서 시작하려면 이러한 각 항목을 정의해야 합니다. 창 크기를 알면 도움이 되는 카메라부터 시작해 보겠습니다.

const width = window.innerWidth; const height = window.innerHeight; const camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(70, width/height, 0.01, 10); camera.position.z = 1;

이제 "상자" 형상과 "메시 법선" 재질이 포함된 기본 큐브를 추가할 장면을 정의할 수 있습니다.

const scene = new THREE.Scene(); const geometry = new THREE.BoxGeometry(0.2, 0.2, 0.2); const material = new THREE.MeshNormalMaterial(); const mesh = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material); scene.add(mesh);

Lastly, we'll instantiate the renderer. (Note that, since we don't provide a rendering target, it will create its own canvas, which we will then need to attach to our document body.) We're using a WebGL renderer here; there are some interesting developments in the THREE world towards supporting a WebGPU renderer, too, which are worth checking out.

const renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer({

"antialias": true

});

renderer.setSize(width, height);

renderer.setAnimationLoop(animate);

document.body.appendChild(renderer.domElement);

We have one more step to add. We pointed the renderer to an animation loop function, which will be responsible for invoking the render function. We'll also use this opportunity to update the state of our scene.

function animate(time) {

mesh.rotation.x = time / 2000;

mesh.rotation.y = time / 1000;

renderer.render(scene, camera);

}

But this won't quite work yet. The singleton context for a web application is the window; we need to define and attach our application state to this context so various methods (like our animate() function) can access the relevant references. (You could embed the functions in our onWindowLoad(), but this doesn't scale very well when you need to start organizing complex logic across multiple modules and other scopes!)

So, we'll add a window-scoped app object that combines the state of our application into a specific object.

window.app = {

"renderer": null,

"scene": null,

"camera": null

};

Now we can update the animate() and onWindowLoad() functions to reference these properties instead. And once you've done that you will see a Vite-driven spinning cube!

Lastly, let's add some camera controls now. There is an "orbit controls" tool built into the THREE release (but not the default export). This is instantiated with the camera and DOM element, and updated each loop. This will give us some basic pan/rotate/zoom ability in our app; we'll add this to our global context (window.app).

import { OrbitControls } from "three/addons/controls/OrbitControls.js";

// ...in animate():

window.app.controls.update();

// ...in onWindowLoad():

window.app.controls = new OrbitControls(window.app.camera, window.app.renderer.domElement);

We'll also add an "axes helper" to visualize coordinate frame verification and debugging inspections.

// ...in onWindowLoad(): app.scene.add(new THREE.AxesHelper(3));

Not bad. We're ready to move on.

Let's pull up what the solar system should look like. In particular, we need to worry about things like coordinates. The farthest object out will be Pluto (or the Kuiper Belt--but we'll use Pluto as a reference). This is 7.3 BILLION kilometers out--which brings up an interesting problem. Surely we can't use near/far coordinates that big in our camera properties!

These are just floating point values, though. The GPU doesn't care if the exponent is 1 or 100. What matters is, that there is sufficient precision between the near and far values to represent and deconflict pixels in the depth buffer when multiple objects overlap. So, we can move the "far" value out to 8e9 (we'll use kilometers for units here) so long as we also bump up the "near" value, which we'll increase to 8e3. This will give our depth buffer plenty of precision to deconflict large-scale objects like planets and moons.

Next we're going to replace our box geometry and mesh normal material with a sphere geometry and a mesh basic material. We'll use a radius of 7e5 (or 700,000 kilometers) for this sphere. We'll also back out our initial camera position to keep up with the new scale of our scene.

// in onWindowLoad():

app.camera.position.x = 1e7;

// ...

const geometry = new THREE.SPhereGEometry(7e5, 32, 32);

const material = new THERE.MeshBasicMaterial({"color": 0xff7700});

You should now see something that looks like the sun floating in the middle of our solar system!

Let's add another sphere to represent our first planet, Mercury. We'll do it by hand for now, but it will become quickly obvious how we want to reusably-implement some sort of shared planet model once we've done it once or twice.

We'll start by doing something similar as we did with the sun--defining a spherical geometry and a single-color material. Then, we'll set some position (based on the orbital radius, or semi-major axis, of Mercury's orbit). Finally, we'll add the planet to the scene. We'll also want (though we don't use it yet) to consider what the angular velocity of that planet's orbit is, once we start animating it. We'll consolidate these behaviors, given this interface, within a factory function that returns a new THREE.Mesh instance.

function buildPlanet(radius, initialPosition, angularVelocity, color) {

const geometry = new THREE.SphereGeometry(radius, 32, 32);

const material = new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial({"color": color});

const mesh = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);

mesh.position.set(initialPosition.x, initialPosition.y, initialPosition.z);

return mesh;

}

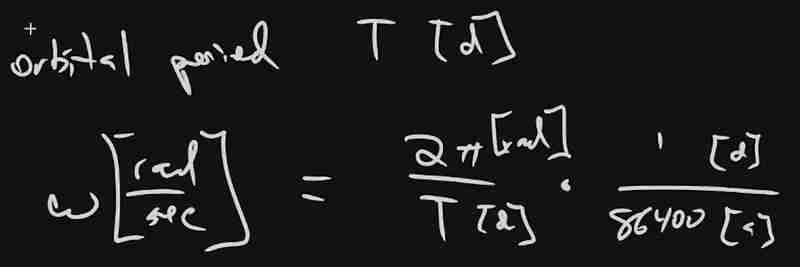

Back in onWindowLoad(), we'll add the planet by calling this function and adding the result to our scene. We'll pass the parameters for Mercury, using a dullish grey for the color. To resolve the angular velocity, which will need to be in radius per second, we'll pass the orbital period (which Wikipedia provides in planet data cards) through a unit conversion:

The resulting call looks something like this:

// ...in onWindowLoad(): window.app.scene.add(buildPlanet(2.4e3, new THREE.Vector3(57.91e6, 0, 0), 2 * Math.PI / 86400 / 87.9691, 0x333333));

(We can also remove the sun rotation calls from the update function at this point.)

If you look at the scene at this point, the sun will look pretty lonely! This is where the realistic scale of the solar system starts becoming an issue. Mercury is small, and compared to the radius of the sun it's still a long way away. So, we'll add a global scaling factor to the radius (to increase it) and the position (to decrease it). This scaling factor will be constant so the relative position of the planets will still be realistic. We'll tweak this value until we are comfortable with how visible our objects are within the scene.

const planetRadiusScale = 1e2;

const planetOrbitScale = 1e-1;

// ...in buildPlanet():

const geometry = new THREE.SphereGeometry(planetRadiusScale * radius, 32, 32);

// ...

mesh.position.set(

planetOrbitScale * initialPosition.x,

planetOrbitScale * initialPosition.y,

planetOrbitScale * initialPosition.z

);

You should now be able to appreciate our Mercury much better!

We now have a reasonably-reusable planetary factory. Let's copy and paste spam a few times to finish fleshing out the "inner" solar system. We'll pull our key values from a combination of Wikipedia and our eyeballs' best guess of some approximate color.

// ...in onWindowLoad(): window.app.scene.add(buildPlanet(2.4e3, new THREE.Vector3(57.91e6, 0, 0), 2 * Math.PI / 86400 / 87.9691, 0x666666)); window.app.scene.add(buildPlanet(6.051e3, new THREE.Vector3(108.21e6, 0, 0), 2 * Math.PI / 86400 / 224.701, 0xaaaa77)); window.app.scene.add(buildPlanet(6.3781e3, new THREE.Vector3(1.49898023e8, 0, 0), 2 * Math.PI / 86400 / 365.256, 0x33bb33)); window.app.scene.add(buildPlanet(3.389e3, new THREE.Vector3(2.27939366e8, 0, 0), 2 * Math.PI / 86400 / 686.980, 0xbb3333));

Hey! Not bad. It's worth putting a little effort into reusable code, isn't it?

But this is still something of a mess. We will have a need to reuse this data, so we shouldn't copy-paste "magic values" like these. Let's pretend the planet data is instead coming from a database somewhere. We'll mock this up by creating a global array of objects that are procedurally parsed to extract our planet models. We'll add some annotations for units while we're at it, as well as a "name" field that we can use later to correlate planets, objects, data, and markup entries.

At the top of the module, then, we'll place the following:

const planets = [

{

"name": "Mercury",

"radius_km": 2.4e3,

"semiMajorAxis_km": 57.91e6,

"orbitalPeriod_days": 87.9691,

"approximateColor_hex": 0x666666

}, {

"name": "Venus",

"radius_km": 6.051e3,

"semiMajorAxis_km": 108.21e6,

"orbitalPeriod_days": 224.701,

"approximateColor_hex": 0xaaaa77

}, {

"name": "Earth",

"radius_km": 6.3781e3,

"semiMajorAxis_km": 1.49898023e8,

"orbitalPeriod_days": 365.256,

"approximateColor_hex": 0x33bb33

}, {

"name": "Mars",

"radius_km": 3.389e3,

"semiMajorAxis_km": 2.27939366e8,

"orbitalPeriod_days": 686.980,

"approximateColor_hex": 0xbb3333

}

];

Now we're ready to iterate through these data items when populating our scene:

// ...in onWindowLoad():

planets.forEach(p => {

window.app.scene.add(buildPlanet(p.radius_km, new THREE.Vector3(p.semiMajorAxis_km, 0, 0), 2 * Math.PI / 86400 / p.orbitalPeriod_days, p.approximateColor_hex));

});

Next we'll add some "orbit traces" that illustrate the path each planet will take during one revolution about the sun. Since (for the time being, until we take into account the specific elliptical orbits of each planet) this is just a circle with a known radius. We'll sample that orbit about one revolution in order to construct a series of points, which we'll use to instantiate a line that is then added to the scene.

This involves the creation of a new factory function, but it can reuse the same iteration and planet models as our planet factory. First, let's define the factory function, which only has one parameter for now:

function buildOrbitTrace(radius) {

const points = [];

const n = 1e2;

for (var i = 0; i < (n = 1); i += 1) {

const ang_rad = 2 * Math.PI * i / n;

points.push(new THREE.Vector3(

planetOrbitScale * radius * Math.cos(ang_rad),

planetOrbitScale * radius * Math.sin(ang_rad),

planetOrbitScale * 0.0

));

}

const geometry = new THREE.BufferGeometry().setFromPoints(points);

const material = new THREE.LineBasicMaterial({

// line shaders are surprisingly tricky, thank goodness for THREE!

"color": 0x555555

});

return new THREE.Line(geometry, material);

}

Now we'll modify the iteration in our onWindowLoad() function to instantiate orbit traces for each planet:

// ...in onWindowLoad():

planets.forEach(p => {

window.app.scene.add(buildPlanet(p.radius_km, new THREE.Vector3(p.semiMajorAxis_km, 0, 0), 2 * Math.PI / 86400 / p.orbitalPeriod_days, p.approximateColor_hex));

window.app.scene.add(buildOrbitTrace(p.semiMajoxAxis_km));

});

Now that we have a more three-dimensional scene, we'll also notice that our axis references are inconsistent. The OrbitControls model assumes y is up, because it looks this up from the default camera frame (LUR, or "look-up-right"). We'll want to adjust this after we initially instantiate the original camera:

// ...in onWindowLoad(): app.camera.position.z = 1e7; app.camera.up.set(0, 0, 1);

Now if you rotate about the center of our solar system with your mouse, you will notice a much more natural motion that stays fixed relative to the orbital plane. And of course you'll see our orbit traces!

Now it's time to think about how we want to fold in the markup for the challenge. Let's take a step back and consider the design for a moment. Let's say there will be a dialog that comes up when you click on a planet. That dialog will present the relevant section of markup, associated via the name attribute of the object that has been clicked.

But that means we need to detect and compute clicks. This will be done with a technique known as "raycasting". Imagine a "ray" that is cast out of your eyeball, into the direction of the mouse cursor. This isn't a natural part of the graphics pipeline, where the transforms are largely coded into the GPU and result exclusively in colored pixels.

In order to back out those positions relative to mouse coordinates, we'll need some tools that handle those transforms for us within the application layer, on the CPU. This "raycaster" will take the current camera state (position, orientation, and frustrum properties) and the current mouse position. It will look through the scene graph and compare (sometimes against a specific collision distance) the distance of those node positions from the mathematical ray that this represents.

Within THREE, fortunately, there are some great built-in tools for doing this. We'll need to add two things to our state: the raycaster itself, and some representation (a 2d vector) of the mouse state.

window.app = {

// ... previous content

"raycaster": null,

"mouse_pos": new THREE.Vector2(0, 0)

};

We'll need to subscribe to movement events within the window to update this mouse position. We'll create a new function, onMouseMove(), and use it to add an event listener in our onWindowLoad() initialization after we create the raycaster:

// ...in onWindowLoad():

window.app.raycaster = new THREE.Raycaster();

window.addEventListener("pointermove", onPointerMove);

Now let's create the listener itself. This simply transforms the [0,1] window coordinates into [-1,1] coordinates used by the camera frame. This is a fairly straightforward pair of equations:

function onPointerMove(event) {

window.app.mouse_pos.x = (event.clientX / window.innerWidth) * 2 - 1;

window.app.mouse_pos.y = (event.clientY / window.innerHeight) * 2 - 1;

}

Finally, we'll add the raycasting calculation to our rendering pass. Technically (if you recall our "three parts of the game loop" model) this is an internal update that is purely a function of game state. But we'll combine the rendering pass and the update calculation for the time being.

// ...in animate():

window.app.raycaster.setFromCamera(window.app.mouse_pos, window.app.camera):

const intersections = window.app.raycaster.intersectObjects(window.app.scene.children);

if (intersections.length > 0) { console.log(intersections); }

Give it a quick try! That's a pretty neat point to take a break.

What have we accomplished here:

We have a representation of the sun and inner solar system

We have reusable factories for both planets and orbit traces

We have basic raycasting for detecting mouse collisions in real time

We have realistic dimensions (with some scaling) in our solar system frame

But we're not done yet! We still need to present the markup in response to those events, and there's a lot more we can add! So, don't be surprised if there's a Part Two that shows up at some point.

위 내용은 [ 무작위 소프트웨어 프로젝트: dev.to Frontend Challenge의 상세 내용입니다. 자세한 내용은 PHP 중국어 웹사이트의 기타 관련 기사를 참조하세요!